I S S U E 10

editorial reflections

Nuzhat Bukhari

—What if . . . think of it

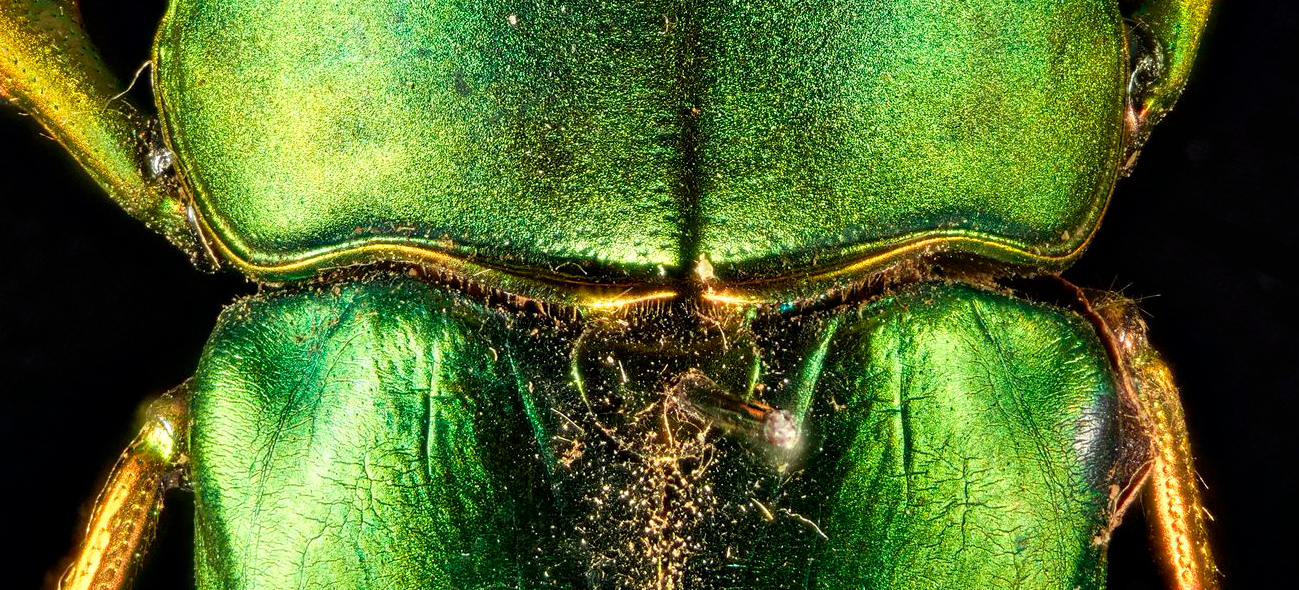

Shakespeare—West Midlands’ genius loci, observed, among other humdrum things, with their inner leanings and gravities, the genus of insects.

Coining a hazardous metaphor in The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke —beetles o’er—an image of antennae overhanging an intimate surrounding space, he evokes his own linguistic practice which hovers over, feeling the sensations of words, pulse-second by second.

Listening to his lines is a stereophonic experience, requiring a skill of watchfulness and hearfulness along the vertical & horizontal axes of the language—upon which momentous consequences may depend.

The hour which illuminated my relationship to drama was when the Royal Shakespeare Company gave an acting master-class and displayed how the same fragment of speech spoken in an altered manner, metric emphasis, rhythmic cadence, spatial context, body gestures, transforms its entire import. Display is a poignant word: from Old French desploiir, unfold, unfasten, spread out, and from Latin displicare, to scatter, with its word-forming element dis- meaning: apart, asunder, in a different direction, between.

This being so evidently so it is equally apposite to the unfurling of all language as a material we work with, even as it works upon us.

Where from does a word emerge into the open air . . . is shaped in ink

on a page.

From whose lungs, lips, fingers.

If we carried a single word through time, touched it as a physical object, walked with it.

One word, a distance, for a long time.

How would our relationship with it be.

An it which should perhaps have the wholeness, even holiness, of a thou. Thou rat, tree, snake, water, rock, human, sky, worm, voice, paper, anima-sounds . . .

—alongside whom I coexist on earth.

Alongside not with because there is the difficulty of withness.

In a letter of May 1997, from Istanbul, Jacques Derrida wrote to a philosopher about her use of the word avec; as in travelling avec him via a correspondence on his journeys—

But with whom? . . . the voyage . . . keep it moving, in and on the doubly abyssal ground of this ‘with [avec],’ apud hoc (apud means ‘next to, in the company of, at the home of,’ but also cum, ‘with, company, community, sharing’). The ‘with’ gives a figure for it and assigns limits to it. As for the other, he or she or it who accompanies me—or never accompanies me—the experience of the voyage (but the experience is the voyage, isn’t it, as the word suggests?), it is in that, as you would say, that I can see coming the beginning or the end of every ‘being-with.’ Therefore I call ‘travelling’ the experience of all experiences, the greatest ordeal, my ultimate question-of-the-other, a question of life and death: whom to travel with? . . . The question seems lodged in the ‘with,’ but it doesn’t stay around anywhere; it remains anxious also, it tosses and turns like an insomniac, it obsesses me in a permanent, concrete, explicit, and literal way . . .

Hamlet’s paradoxes, punnings, witty pretendings are a method to undo unbearable verbal banalities; Derrida might term them transvérités (cross- truths).

Quentin Skinner calls it a ‘forensic eloquence’, a ‘judicial oratory’ Shakespeare is attuned with. And he ‘spills’ into the play an intricate form of constitutio coniecturalis wherein a ‘speaker aims to employ conjecture to uncover some hidden truth’—

Polonius: . . . – what do you read . . . ?

Hamlet: Words, words, words.

Polonius: What is the matter . . . ?

Hamlet: Between who?

Polonius: I mean the matter that you read . . .

Matter is both a term used by vernacular rhetoricians and in a judicial context.

Hamlet’s matter is his mother and both words share the same origin mater, meaning material and core.

Failure to make sorrow a matter, to make it sufficiently matter, is the marrow of Hamlet’s maddened mind.

In Latin the word grief is gravis, weighty.

An entangled root it shares with grace, disgrace, aggrieve, aggravate, even with poet, singer, praise.

With their prismatic facets words make weighty demands on us. Hamlet will disgrace, aggrieve those who will not pay observance to death.

He will create mortal, moral carnage from a failed principle of conduct. Take a word and unmake a world from within it.

Human minds can wrest things out of shape, which may be a wonder,

a blunder . . .

In Hamlet observe a cloud and create a camel, a weasel, a whale out of it . . . The prince bends his thinking to make language form estranged patterns . . .

In Antony & Cleopatra, Shakespeare ponders clouds again, this time as—dragonish, as a horse, and most evocatively As water is in water—because to transmute language with language is coterminous to an element like water to shape water . . .

In Rome on Keats’ gravestone—Here lies One whose Name was writ in Water . . .

Not on but in. With writ writ in lower-case.

Keats wrote his epitaph and knew a name, even a Name, can be overwhelmed by water.

When Shelley drowned at sea a volume of Keats’ final poems was found in his inner pocket.

Though Keats will also have known that epi in the word epitaph meant close upon (in time, space), and its taphos meant a tomb.

To write his own name in water was to enter not internment but infinity—

Horatio will offer a caveat to a mutually hallucinating Hamlet—‘What if . . . ’ this spectre of his father:

What if it tempt you toward the flood my lord,

Or to the dreadful summit of the cliff

That beetles o’er his base into the sea,

And there assume some other horrible form

Which might deprive your sovereignty of reason,

And draw you into madness? Think of it.

(Act 1:4:69–74)

It is a trifling word it, but how much it holds, folds and scolds into itself as it self-generates an agitated largo tone and tempo in the tight momentum, enclosure of this speech.

First comes the it of the ghost

Then the it of the chain of tragedies it may lead to

The flood, cliff’s edge, deforming sea

If the it of the ghost exists at all

Disconcertingly, we must Think of it all at once

If the it is a collective phantasm of traumatised minds?

The metamorphic capacity of it leading to the pull and play of insanity . . .

‘Within’ what Hamlet calls the ‘book and volume of my brain’ . . .

Volume isn’t a safe word here, from volvere, to turn around, roll;

Hamlet’s syntax is a beautiful fusion of what Polonius calls this

‘encompassment and drift of question’ and Claudius a ‘drift of

circumstance’ . . .

a circumlocutory rumination . . .

with the sudden capacity of a volte-face arriving at a naked precision.

Here even book is a raw, internal thing (it originates from bokiz the inside

bark of beech trees on which runes were inscribed).

Hamlet amplifies the volume in his head and heart of every felt facet of

life—

If you have ever heard a hallucinatory voice—it booms lightly . . .

is a physical force

like sound blowing softly from a giant speaker across a vast room . . .

After line 74 above, in the second quarto of the text, Shakespeare had four lines which he deleted from the later folio, among them this—‘The very place puts toys of desperation . . . into every brain . . . ’ toys of desperation are whims of mental behaviour.

Shakespeare’s master-stroke in Hamlet is to enclose a play within the play which plays on the metafictional games, trickery, self-trickery we play not only in books but also in our own brains and in the heads of others until we no longer know a cardinal truth from an imposed reality (as if a distinction cannot be made between the two).

Hamlet will tell Guildenstern that playing a musical instrument—

’Tis easy as lying. Govern these ventages with your fingers and thumb, give it breath with your mouth, and it will discourse most eloquent music.

And his tone is raised in pitch with this devastating assertion of the equation between art and life as equivalent forms of a false performance:

Why look you now how unworthy a thing you make of me. You would play upon me, you would seem to know my stops, you would pluck out the heart of my mystery, you would sound me from my lowest note to the top of my compass—and there is much music, excellent voice, in this little organ, yet cannot you make it speak. ‘Sblood, do you think I am easier to be played than a pipe? Call me what instrument you will, though you can fret me, you cannot play upon me.

(Act 3: ii: 329ff)

—frets are the raised bars for fingering on the necks of some stringed instruments, a guitar, a lute . . .

but Hamlet is also fretting over his own fate

which he is instrumental in reforging without societal forgery.

The play is designed to ensnare Claudius, the killer of his father.

As mock-conductor Hamlet asks the actors to speak their lines ‘trippingly on the tongue’—trip is a semantic kin of trap.

Freudian slips of the tongue trip the speaker and trap a snip

of their unconscious.

A drama within this drama (which must make us ask what this playwright is playing at) showing us deflectedly the dubious boundaries between actor and audience both inside the outer play and within the inner play but also both plays with the audience inside and outside it.

Look at this elated self-reflexivity from Hamlet as a director:

Why, what an ass am I! . . .

Must like a whore unpack my heart with words . . .

All the world’s a stage, a brothel, a staged-brothel.

Hamlet the play is like Chinese boxes.

But so is Hamlet the persona.

It is as if the invisible skein of theatre’s ‘fourth wall’ is torn down and the solitude of the spectator exposed and imposed upon in a Brechtian strategy of deconstruction.

Shakespeare now preempts a future spectacle of alienation.

What if it tempt you . . . Horatio has asked.

The proximity of the what to the if then to it makes the simmering premise of the speech slippery, as images sidle, slide, dissolve like spectres . . .

Let me, pleasurably, indulge in saying that if derives from the Old English word gif.

The initial g was then pronounced with a sound close to the Modern English y.

So that it would be spoken as yif.

As if sonically conflating a you with an if.

Giving ontological gusto and tension to existence.

Sometimes a word can strike through space like a zagged path of lightning whose brief electric charge reminds us of how immediacy touches infinity.

Or the legacy of a word is like deep veins in stones.

An immutable and inevitable trail . . .

If I’m exulting in this it is because yif is central to this play.

The minutiae of an if and a you coalescing inside the epically public concept we know as tragedy:

To be, or not to be

The brief pause created by the virgula (in Latin meaning a little twig, the comma) is actually a breathtaking chasm between life and death.

This little twig in the syntax is frequently neglected or omitted.

In my Cambridge edition of Hamlet the text includes it but the editorial essay by the editor omits it.

I don’t wish to get hyper about a typo but an error or an omission in such a momentous moment of indecisive terror is the twig which tethers Hamlet to the tree, however rotted he conceives it to be:

Something is rotten in the state . . .

A comma is also a caesura, a fissure between the acting out of choices

—a metrical and ethical pause—

Hamlet plays upon punctuation too:

As peace should still her wheaten garland wear,

And stand a comma ’tween their amities

Puttenham in his Art of English Poesy, 1589 defines the comma as ‘the shortest pause or intermission’, but Hamlet knows what can occur in ‘one’ second:

It will be short. The interim’s mine,

And a man’s life’s no more than to say ‘one’.

Hamlet eyes the judgment of eternity on suicides and murderers

so other ‘enterprises of great pitch and moment’

lose their value in the macrocosm of the soul:

‘Conscience does make cowards of us all’ . . .

Hamlet can balance a thought between an instant and infinity . . .

A dictionary tells us, sans any irony:

The modern verb to be in its entirety represents the merger of two once-distinct verbs, the ‹b-root› represented by be and the am/ was verb, which was itself a conglomerate. Roger Lass (Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion) describes the verb as ‘a collection of semantically related paradigm fragments,’ while Weekley calls it ‘an accidental conglomeration from the different Old English dial[ect]s.’ It is the most irregular verb in Modern English and the most common.

And Hamlet conceives his condition structurally:

The time is out of joint: O curséd spite,

That ever I was born to set it right.

Time is a physical body and he persuades himself into being a kind of philosophic chiropractioner (chiro- ‘hand’ + praktikos ‘practical’)—to reset a disjointed immoral body of society by taking societal and metaphysical situations into his own hands.

Look at and hear the unnerving rhyme of revenge—spite, right. It is an extravagantly self-justified assertion.

Not as uncommon then or now as one might imagine.

Thinking and memory are phantasmal an it of consciousness we still cannot fathom . . .

But how, Horatio, is reason to be summoned when the very instrument creating it is so prone to untune itself—?

Textured switches can happen swiftly in finite lexical spaces in Shakespeare.

Only rarely can actors follow the mutable emotional rhythms of his lines. As also happens in his compositional counterpart Shostakovich.

Grief deranged Lear holds a feather to a dead daughter Cordelia’s lips and if—

‘This feather stirs. She lives.’

Feather, feat, father, eat, her.

Death will eat her.

Lear’s emotional feat as a father.

Fea–r locked inside the word Feather.

Shakespeare’s quill will kill her.

Everything enfolded in the wing of one apparently light word.

Begun during 1941 in Leningrad and performed on August 9th 1942, Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 in C major, Opus 60, was written when German troops besieged the city, Russian citizens were starved to the point of cannibalism, emaciated musician soldiers were recalled from the Front to join the orchestra, the bombardment temporarily paused for the performance so that its defiant broadcast could be heard by the fascists. The score itself was transported in a special aircraft that flew around the blockade to reach the city.

In ‘Reminiscences’ the second movement of this symphony, the harps make their first appearance with an attempt to console the ear and soul, all the while the rhythms of the flutes continue quite unaffected by them and a solitary bass clarinet plays the melody bleakly,

its sound drifting out into an almost nihilistic future . . .

The music of what happens too is a mesh of cross-grained layers . . .

The departing ghost invokes Hamlet ‘Remember me’ . . .

The son plays variations on the word which holds in this passage its full

resonance—a tenuto note . . .

Words like single musical notes reverberate:

Remember thee?

Ay thou poor ghost, whiles memory holds a seat

In this distracted globe. Remember thee?

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain,

Unmixed with baser matter: yes, by heaven!

O most pernicious woman!

O villain, villain, smiling damnèd villain!;

My tables – meet it is I set it down

That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain;

At least I’m sure it may be so in Denmark.[Writing]

So uncle, there you are. Now to my word:

It is ‘Adieu, adieu, remember me.’

I have sworn’t.

(Act 1: 5: 95ff)

It prempts that talismanic To be, or not to be speech, where Hamlet concludes—‘Be all my sins remembered’.

He is obsessed with re-membering—the word originates in the Latin member, limb and flesh, sex organs, with Christian implications of a member of the Church as the body of Christ—all at the heart of Hamlet’s thoughts of sinful adultery, a refusal to accept the act.

The re prefix as a word-forming element always means a return, conveying a notion of undoing.

How do we undo what we’ve done.

How do we undo what is done to us.

There’s a German compound word—Vergangenheitsbewältigung—‘coming to terms with the past’—sometimes translated as a ‘struggle with coming to terms with the past’—which seems closer to the condition of it.

Drama itself is from Classical Greek drāo ‘to do, make, act, perform’ (especially some deed).

What . . if . . of . . it . .

Shakespeare knew the import and weight of minuscule most

commonplace of words and asks us to think of it.

When Gertrude asks her son Hamlet:

Why seems it so particular with thee?

The son swings the word back to her:

Seems madam? nay it is, I know not seems.

Hamlet’s mind beetles in and out of the linear logic of subjects.

He habitually turns the garment of language inside out,

peering under its outer finish to show us how the pattern is fitted,

the inner seams sewn, the roughly tacked lines of a thought,

the stitches of a sentence, a sentiment or a word.

Even if he is accused by Claudius

‘Get from him why he puts on this confusion’ . . .

As if one wears language as a costume.

Seems might seem a seemingly seamless word but it isn’t all that it at first seems.

The verb seem is derived from Old Norse soema: to honor; put up with; conform to, and also from the adjective soemr, ‘fitting’.

Hamlet resists a superficial fitting-in.

He will not be fitted-out in the garments of the diplomatic, honourable son.

Moreover, the word is reconstituted from Proto-Germanic somiz (source also of Old English som ‘agreement, reconciliation’, seman ‘to conciliate’ source of Middle English semen ‘to settle a dispute’).

The son is unseemly, disputitious, irreconciable, disagreeable, not conciliate.

He knows not seems however unseemly this at first or at last appears to be.

Performance is, as every writer and actor knows, unseemly.

Shakespeare knows his trade.

Early in Hamlet the tragedy is already presaged. As in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Hamlet begins with a seemingly banal exchange between two house guards:

Bernardo: Who’s there?

Francisco: Nay answer me. Stand and unfold yourself.

There’s a preconception amongst many writers that moral clarity, even (gasp, horror) moral judgement, is an antagonist of a complex literary sensibility. The two things need not be mutually exclusive.

In his essay ‘On Translating Paul Celan’, Michael Hamburger writes—

In a letter he wrote to me in 1957 (Celan) was still able to apologise for having harped on one of his successive crises throughout a recent meeting between us, when he was obsessed with what he felt to be a publisher’s betrayal of him to his enemies only because the firm had decided to issue a book by a ballad-writer popular during the Third Reich, a decision that caused him to leave that publisher.

—Celan’s Jewish family had been murdered by the Nazis. It was the permanent shadow across his body and mind (which he ended by suicide).

It is painful to read Hamburger’s equivocal words harped on, obsessed with, what he felt to be, betrayal of him, only because.

As a poet, Celan shows us that practical ethics and the highest skills in art are not incompatible forms of existence.

In fact being in the word and being in the world are in an intimate dynamic entanglement.

Submitting to the expediency of a convenient neglect or a conscious evasion is commonplace.

Those, like Hamlet, Celan, and others throughout history, ask us

to remember them.

Society and culture itself embarrasses, if not ostracizes, us out of

our deepest preoccupations.

Art offers not a redressal but an answering voice to such external pressures.

In my book, Brilliant Corners, I wrote a poem called ‘Pathology’, a conversation with my father as his body lay in the mortuary. He was alive at the time.

I had seen the miniature sculpture by Ron Mueck Dead Dad—

a naked man lying on a plain slab.

I hadn’t read a poem like it so I wrote it.

The word pathology comes from the ancient Greek word pathos, suffering, and logia, study.

My father was an adulterer. A serial adulterer. An unapologetic

and self-justifying one.

The fact that this story is shot through with race, a white working-class Christian woman, adds another layer of complexity to it.

The poem is a soliloquy on what loss, deception, irresponsibility feels like, the sense of injustice and betrayal of it.

I imagined a catharsis in writing the poem.

But art is not so redeeming.

There’s guilt involved even in artistic truth.

In any truth-telling, because the memory of the wound is opened

and injuries are again felt.

This is a strange function of literature.

I would like to think that it is also a possibility in personal life

and civic space.

That we aren’t censored clean of our most uncomforting thoughts.

There’s a grim and crucial turn to this. A head-on collision between art and life.

On the late Friday afternoon he died, while I was swimming and he was slowly dying, late that night the woman who had trapped my father sent me a message to inform me.

She had read my poem and was ‘very upset’ at being called a ‘whore’ in it.

She accused me of being ‘resentful’ and made no apology for her adulterous acts.

Jean Améry, a survivor of Auschwitz & a profound intellectual, wrote against, and to, the ‘social body’:

‘But my resentments are there in order

that the crime becomes a moral reality for the criminal, in order

that he be swept into the truth of his atrocity.’

(Hamlet is accused of being resentful: root of resent is sentire ‘to feel, think’).

His body barely cold she was ready to defend herself.

How do you encounter a real death when you’ve imagined a death on paper.

My answer to this is clear:

There is a chasm between the poem I wrote and the actual death.

The artist must inhabit this wide gap almost like a ghost.

Or a conscience.

I would not stand in a room with a corpse and talk to it.

(As Marlon Brando does to Rosa his wife in Last Tango in Paris. One of the most spectacular acting scenes in cinema)

I would want the person to hear me.

So there is something of the spectres in our consciousness which we value and the appearances of which we call art, music, literature.

But on the facing page to ‘Pathology’ I placed this brief poem:

Othello

The price of anything is eternal vigilance –Christopher Ricks

Betrayal: his soul’s lacuna.

Its rhizome.

A handkerchief’s

intemperate blank page.

There’s magic in the web of it.

And carnage.

—Othello’s obsessive vigilance upon his wife fails in self-vigilance which segues into a self-deception over and above the imagined deception of his wife.

It is his own rampant rhetoric which leads him to commit a homicide. Rhetoric can be a radical art of persuasion or a recursive one of a deflection from reality.

I’m not establishing an equivalence between these plays and my life but there is an equipollence which readers draw upon from art. Artful minds can fail themselves and need self-correctives.

Art, and we, must ask,

What if . . . think of it . . .

We exist in the grey zones of moral choices.

And can cross the boundary as effortlessly as a shadow moving imperceptibly across us unknown to us until we stand in an embodied darkness.

§

In his profound book Ich und Du (I and Thou) published in 1923, the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, a thinker who believed in the cardinally distinctive yet coterminous relationship between Jews and Arabs, writes the following—

This is the eternal origin of art that a human being confronts a form that wants to become a work through him. Not a figment of his soul but something that appears to the soul and demands the soul’s creative power. What is required is a deed that a man does with his whole being; if he commits it and speaks with his being the basic word to the form that appears, then the creative power is released and the work comes into being.

The deed involves a sacrifice and a risk. The sacrifice: infinite possibility is surrendered on the altar of the form; all that but a moment ago floated playfully through one’s perspective has to be exterminated; none of it may penetrate into the work; the exclusiveness of such a confrontation demands this. The risk: the basic word can only be spoken with one’s whole being; whoever commits himself may not hold back part of himself; and the work does not permit me, as a tree or man might, to seek relaxation in the It-world; it is imperious: if I do not serve it properly, it breaks, or it breaks me.

The form that confronts me I cannot experience nor describe; I can only actualize it. And yet I see it, radiant in the splendour of the confrontation, far more clearly than all clarity of the experienced world. Not as a thing among the ‘internal’ things, not as a figment of the ‘imagination,’ but as what is present. Tested for its objectivity, the form is not ‘there’ at all; but what can equal its presence? And it is an actual relation: it acts on me as I act on it.

As Hamlet proceeds the ghost recedes until it becomes the sole presence of Hamlet’s inner vision, unconscious.

Which is what it always was.

Hamlet the man becomes an artful murderer but a murderer nonetheless. I believe that for all his splendour, his tragedy is in first confusing and then confuting the relationship between art and life, as Buber so strenuously illuminates.

By mirroring Claudius’ murderous act in Hamlet’s play within the play, and irresolutely disrupting the inner play’s plot at this pivotal point, Shakespeare spares himself any retributive, or redemptive, phantasmagoria about his own art.

Hamlet, as a name, in itself has the Proto-Indo-European root tkei from the Sanskrit kseti meaning to abide, dwell and from which both the words home and haunt also emerge. Hamlet dwells in words which are spectres in his mind . . .

It is a coincidence of value to know that Martin Buber as a child was abandoned by his mother; a trauma he shares with Hamlet. David Aberbach has recently said of Buber, ‘His sensitivity to the corruption and breakdown of social and political attachments had a distinctly personal origin.’ His biographer Maurice Friedman describes the loss as the ‘decisive experience of his life, without which neither his early seeking for unity nor his later focus on dialogue and with the meeting with the ‘eternal Thou’ is understandable.’

It is as if both Hamlet and Buber saw their universe in a grain of sand and in the gram of a word.

§

Shakespeare knew about the weight of a feather and the weight of his quill pen.

In ‘Running Fence’ which ruminates on borders, I wrote this in the penultimate stanza which, with the world in a catastrophic moral crisis of weathers and wars, seems apposite:

Waves hurtle, unnail timber, butt doors. Houses unanchor,

drift to sea as lopsided boats. Snow-curtains coil for miles,

capture cities in ice-nets, blot-out maps, make folds

in winds legible. Land-wrinkles like sheets of weathered paper.

The ancient Egyptians poised a person’s heart against a feather.

If a heart was lighter than a plume, gods allowed them to ferry

into a land of souls. A feather-tuft’s heaviness is of rose ashes,

not a rose.

Our scales waver, the weight wanders—

§

Coda (a)

The score paper on which Shostakovich inscribed his Leningrad symphony was imported from Istanbul.

The Chrysomelidae beetle likely arrived across Western Europe via American military bases in France during World War 1.

The communist government of East Germany accused the U.S. of dropping these insects, dubbed Amikäfer, Yankee beetles, out of low-flying airplanes to sabotage their potato harvests.

The minuscule, destructive Emerald Ash Borer beetle Buprestidae, native to northeastern Asia, likely came into America and Ontario in wood-packing material from Asian trade.

Coda (b)

Wittgenstein, in his Tractatus, remarks on philosophy:

It should delimit the thinkable and thereby the unthinkable.

It should limit the unthinkable from within through the thinkable.

§