I S S U E 6

On Performance & A Little Devil in America

Yomi Ṣode unspools memories and musings prompted by Hanif Abdurraqib’s A Little Devil in America, a new book of history and memoir exploring Black performance

1998.

My mum bought me a new pair of rollerblades, black and dark blue with two buckles that you click then fasten to the point of feeling both feet swell in agony. My blades and my flattop, glistening with the blue, Blue Magic. The scent, so strong that it would last until night and someone might wonder if you were just starting your day, strong. No one forced me, that afternoon, to skate down the ramp adjacent to the parked double-decker bus filled with girls, but I felt like—what better way to make an entrance, than this?

◉

◉

Hanif Abduraqqib is a poet, essayist, a cultural, and musical critic—and a damn good tweeter! I have been a fan of Hanif’s work for some time, from ‘They can’t kill us until they kill us’, ‘The crown ain’t worth that much’, to ‘Go ahead in the rain’. When Debo Amon asked if I would be interested in having a conversation with Hanif regarding his new collection of essays, titled A Little Devil in America (ALDIA) we had a mutual moment of excitement, fanboying and expletives.

◉

ALDIA is a poetic, lyrical narrative. It’s history and a memoir, a hymn in praise of Black performance. It delves into masculinity, the intimacy that exists when artists beef and why it happens, and the part that gentrification plays in the erasure of iconic Black figures. It looks at representation, societal pressures, and bravery through the stories of Don Cornelius and Soul Train, Beyonce, Dave Chappelle, Josephine Baker, Wu Tang Clan, Whitney Houston, and more. All this interspersed with Abdurraqib’s own story and analysis of the act of performance, and how (to some degree) it affects our day-to-day thinking, interactions, and most importantly, how it shapes society as a whole.

◉

This book and how it made me feel will stay with me for a long time. Hanif writes Magic tricks all have extremes, but there is so often some movement of the trick that requires sacrifice. A field of dead crows; a trashcan full of playing card fragments. Or the commitment of killing off your whole self so that another version of you can live for an audience’s approval. I think about Blackness as a whole and (optimistically or not) when it’s going to stop being an issue. In relation to the arts, there’s this constant battle with the mainstream industry versus the bubbling conversation within the Black community. I’d like to believe the artists mentioned in the book have enjoyed their careers, but in places, it left me feeling sad and contemplative.

◉

1998.

My botched attempt at being either Torvill or Dean, on concrete, came to a humiliating end in front of that double-decker bus. How else could this have ended? I had no idea how the brakes worked at such speed, but if God loved a trier, then my hope that afternoon, on the ramp at Elephant & Castle, underneath the mounted pink elephant, would have been that a blessing be bestowed upon me, post the crash, the burn, and yes—the performance.

◉

Two days before the conversation with Hanif I questioned whether I needed to change the way I hosted talks. Usually, my interviews are very hype. I use airhorns, explosions, lasers, you name it. This was a format that I developed during lockdown, in 2020, as a way to catch the attention of the audience and keep them entertained. My use of air horns is a direct result of experiencing the sound systems at Notting Hill Carnival; something about the loudness, what a klaxon did to the masses that caught their attention. I loved the ruckus it caused. I also remember tuning into pirate radio as a teenager, hearing the sound fx and the DJ abruptly talking every 20 seconds while the tune was still playing. All a performance. In relation to my tweet earlier, the breaks I took were for reflection and to interrogate my own performance in life. How much of me do I kill in order to garner approval or validation? In other words, are people looking forward to me speaking to artists, or do they want to be entertained by me pressing random air horns from time to time? After reading the chapter titled ‘This One Goes Out to All Of the Magical Negroes’, I became fixated on this interrogation while editing my forthcoming book, Manorism, and questioned whether the publicist only booked me because I was one of these mythical beings. It took me until the day of the conversation to fully shake that feeling off.

While I’m mid-talk with Hanif, laughing as lasers go off, we touch on the role of the writer in relation to performance towards one’s own community and/or the mainstream. Hanif talks about the familiarity of the community that surrounds him. How they all know his face and name, whether it is walking down the road or visiting his local convenience store. I am reminded of the community I serve. My Yoruba tutor for example, who after four years of me avoiding him due to sheer confidence issues, texts, ‘Abayomi! Ku ọjọmẹta. Se alaafia ni? Ile nkọ? Poetry nkọ?’ Or some of my mandem, who don’t always understand the beauty, intricacies or complexities of poetry, but are still on hand with, ‘Bro, how’s the poetry ting going?’ The people that don’t require me to perform, because they have already invested in my dream as a writer. When I win, they win. My story is their story and they know it’s in safe hands. I believe it’s this community that Hanif has in mind when he writes that Showing off [is] something you do for the world at large and showing out is something you do strictly for your people. Meaning, whenever I step out, I do so with them in mind. Even now in my writing journey, I think about these worlds. I think about the part that I play when, in the past, I’ve sat in more formal literary settings and snooty comments are made about the open mic scene or Spoken Word, knowing the majority of my development grew from there. I question those early points of silence, the fear of not being taken seriously as a writer, my performance when moulding myself into something I was not. I wondered who this best served, the sacrifice and cost of the performance in relation to climbing the ladder towards one’s perception of success. At the heart of this, what matters is the work I make not who it’s written/performed for. These principles are my guardrails ensuring that I stick to stories and experiences that I want to share as opposed to the things that I feel people want to hear.

◉

2013.

When I started, I spent a lot of time on the open mic scene. Whether you were a rapper, singer, comedian, or poet, you would have a band there ready for any instructions to bring your performance more to life. The Remedies became the band that I built a lot of my earlier work with, fusing poetry and live music. Now, we had been booked to perform at Wireless festival. This was our biggest gig to date. I had my face on the app’s schedule and had people walking over, waiting for us to start. By this point, I had an album and an EP to my catalogue but this gig would be the last time I performed my music on stage.

The main question at that point (especially from the band) was why? Why hang the boots up when we just received a really good booking? For me, it was an easy decision to make. As much as I enjoyed making music, I could feel a greater calling knocking and my door. I wanted to be a better writer and in order to do that, I felt like I needed to start from scratch. I stopped performing completely and enrolled on a variety of evening poetry courses for the following year. By 2015, I was at The Roundhouse in Camden performing COAT, my first poetic theatre, solo show to a sold-out audience.

◉

Hanif has the ability to seamlessly weave a story within a story; a history of dance marathons during depression-era America is merged with stories about lunchtime dances in his high school auditorium and moves to Don Cornelius’ Soul Train and seeing himself represented on TV. There’s a powerful juxtaposition between white people fainting after hours of dancing at dance marathons for a trophy and Soul Train, watching Black people dance for liberation, for freedom and survival. His process of writing is as if he is tying a present with a ribbon; covering the core to secure its structure, tying a bow in the middle, and placing it in our hands. This book is a present that slowly unravels. A game of pass the parcel with a gift under each new layer. The more I read, the more historical context I am understanding, the more I’m like Fam, that line is Fire!

The moonwalk is all about trying to run from the past when its hands keep dragging you back

or

After all, what is endurance to a people who have already endured

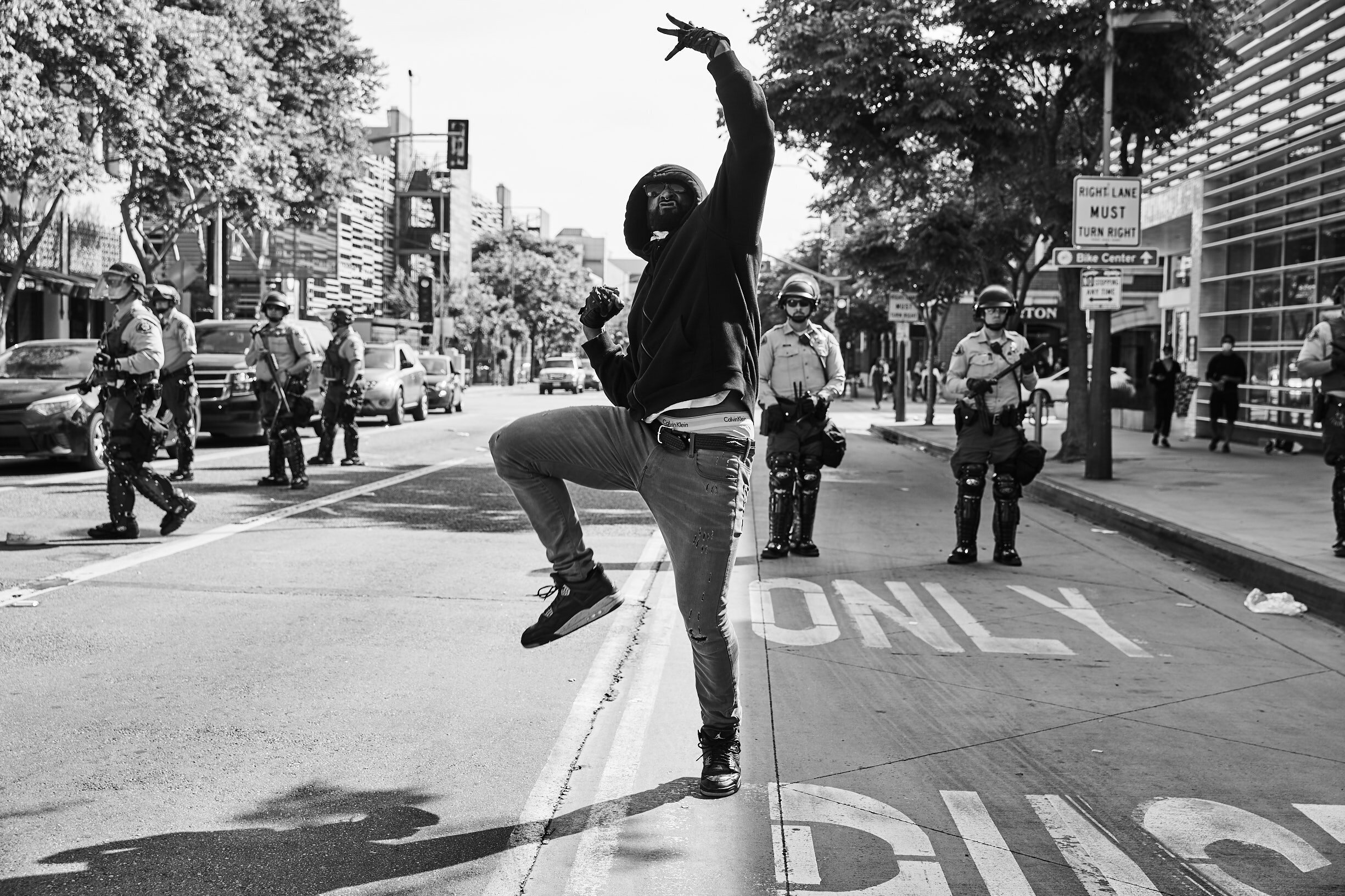

And when speaking about endurance, I wonder what Hanif’s threshold is? Death was a theme that I picked up on but I never got to speak to him about it. The title, taken from movie star and entertainer Josephine Baker’s speech at the March on Washington feels like a legacy left to Black people in America; a mantle to take up. Black people have always danced. We dance for births, deaths, weddings, christenings, marches. Every major milestone is celebrated with movement. From as far back as the clog, the Juba dance, swing, Charleston. To my elders in hall parties doing the money dance, to the Dougie, Milly rock, and bringing it closer to my sides—the two-finger garage skank, the gun finger, and the lean and bop. There is an easiness when it comes to us and expression, many cultures misunderstand this, some are scared of it, and it is that same fear of our expression that has resulted in so many of us being murdered at the hands of the police.

◉

Jo’Artis Ratti krumps in front of a line of police officers on May 31 2020 in Santa Monica. (Pip Cowley)

◉

With this book, what Hanif manages to capture are feelings of celebration and mourning, activism and pockets of joy, all the while magnifying the legacies of Black artists. I never asked Hanif about responsibility, whether he feels the path he walks now is due to the sacrifice and bravery of the names he mentioned in this book and if he feels he now holds that mantle as a writer in paying it forward. Maybe that is a pressure that I feel myself in knowing the Black poets before me and what they went through so that I could inhabit these spaces as opposed to simply occupying them—like Hanif and the artists he cites—their stories and experiences now live through me.

◉

Jo’Artis Ratti, May 31 2020, Santa Monica. (Pip Cowley)

Yomi Ṣode’s debut collection Manorism will be published by Penguin next year.

This essay appears in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of Poetry Birmingham; you can buy the issue here.